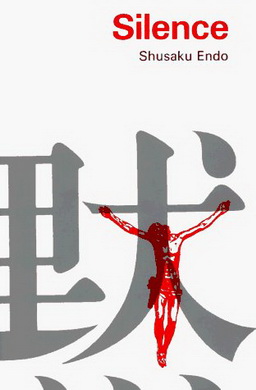

Book Review: Silence by Sūshaku Endō

Except for Barabbas this is the only Christian novel I’ve read. And it’s a Christian novel from another side of the globe from Barabbas.

Except for Barabbas this is the only Christian novel I’ve read. And it’s a Christian novel from another side of the globe from Barabbas.

While this novel has been labelled as a novel about the atrocious persecution of Christians in Japan, to my understanding that is a backdrop, a very important backdrop, but backdrop still. It’s also very complex. Official view about Christianity and elaborate tortures, the metamorphosis of the faith in the Japanese soil, the people, places, and nature… It’s not a black and white story of oppression.

This is predominantly a novel about Christian sympathy. A person’s journey through suffering to understand what it meant to Christ, what sort of shepherd he was. The central character (a priest) has gone through what we can say ‘a dark night of the soul’. The crisis was acute. Suffering raised questions that in other times can be considered blasphemous. This crisis is the origin of the name of this book. The unbearable silence of God in the face of the unbearable agony of layman Christians was a recurring theme. A particularly beautiful example of this crisis is:

What do I want to say? I myself do not quite understand. Only that today, when for the glory of God Mokichi and Ichizo moaned, suffered and died, I cannot bear the monotonous sound of the dark sea gnawing at the shore. Behind the depressing silence of this sea, the silence of God. … the feeling that while men raise their voices in anguish God remains with folded arms, silent.

It, in time, led the priest into doubt if God exists at all. Of course, his training in the seminary won.

What I liked about this book is, how the priest was officially apostatized. He hasn’t been broken down in extreme situations. Neither threat nor persuasion could convince him to apostatize. What convinced him is a deeper, more beautiful interpretation of the Christian faith. He found that even Christ himself would’ve been apostatized if it saved some souls from suffering.

‘Don’t deceive yourself! ’ said Ferreira. ‘Don’t disguise your own weakness with those beautiful words.’

‘My weakness? ’ The priest shook his head; yet he had no self-confidence. ‘What do you mean? It’s because I believe in the salvation of these people … ’

‘You make yourself more important than them. You are preoccupied with your own salvation. If you say that you will apostatize, those people will be taken out of the pit. They will be saved from suffering. And you refuse to do so. It’s because you dread to betray the Church. You dread to be the dregs of the Church, like me. ’

Until now Ferreira’s words had burst out as a single breath of anger, but now his voice gradually weakened as he said: ‘Yet I was the same as you. On that cold, black night I, too, was as you are now. And yet is your way of acting love? A priest ought to live in imitation of Christ. If Christ were here … ’ For a moment Ferreira remained silent; then he suddenly broke out in a strong voice: ‘Certainly Christ would have apostatized for them. ’

This was the end of his dark night of the soul. The new dawn was not a dawn devoid of faith. Quite the contrary. It was a dawn bringing a faith deeper than anything he have ever learned.

Since I have not read it in Japanese, I can’t really talk about Endō’s writing quality with much confidence. However, I think readers will agree with me on his ability to create symbolic archetypal characters whose importance lies in their manifestation of one quality, or vice, or a crisis. Over and over again throughout the book, they play the same role of a coward, kind, or heroic person. The book contains some very powerful characters like this.

His intellectual honesty is particularly praiseworthy. He understood the problem of a foreign religion such as Christianity must face in a culture that is in many cases diametrically opposite to Europe. Brutality and suppression are only side-effects. The problem is deeper and Endō faced it with much sincerity.